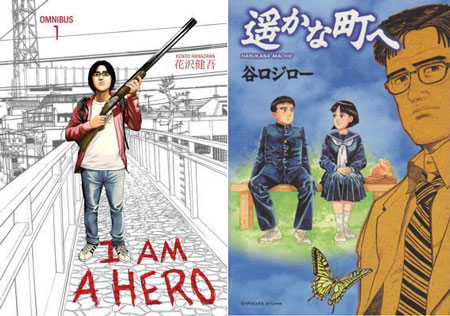

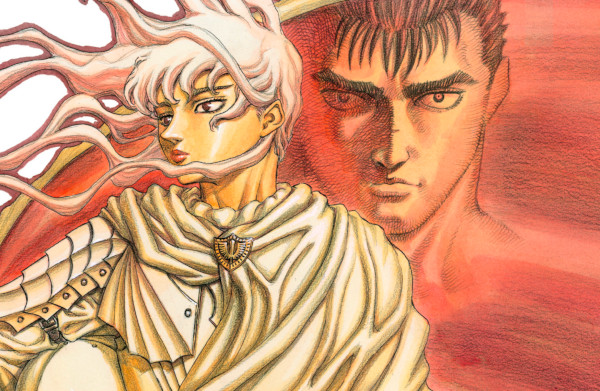

Berserk volume 12 left us at a crucial point: The Band of the Hawk were to be sacrificed so that Griffith can join the Godhand. Horrified, Tim and Kumar moved quickly on to volume 13, which left us… horrified, in a less fun way. Casca is raped, in an unnecessarily long, confusing, and (ick) titillating scene (and we have to talk about it, so be warned).

The rest of 13 and the start of 14 finally bring us up to the status quo of the first 2 1/2 volumes, and get us started on a new story of Guts and Puck which…. doesn’t seem to move the story forward at all. While there are good points, our feelings about Kentaro Miura‘s series have become more complicated. And, by the way, how necessary was this 11-volume flashback?

Brought to you by:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Most people have some dreams of fame and fortune. A certain portion of those people make their way to Hollywood in hopes of getting that big break. But how much are you willing to give up to achieve that goal? And what if the fame isn’t as great as you expected? These are the questions arising from the forthcoming graphic novel

Most people have some dreams of fame and fortune. A certain portion of those people make their way to Hollywood in hopes of getting that big break. But how much are you willing to give up to achieve that goal? And what if the fame isn’t as great as you expected? These are the questions arising from the forthcoming graphic novel