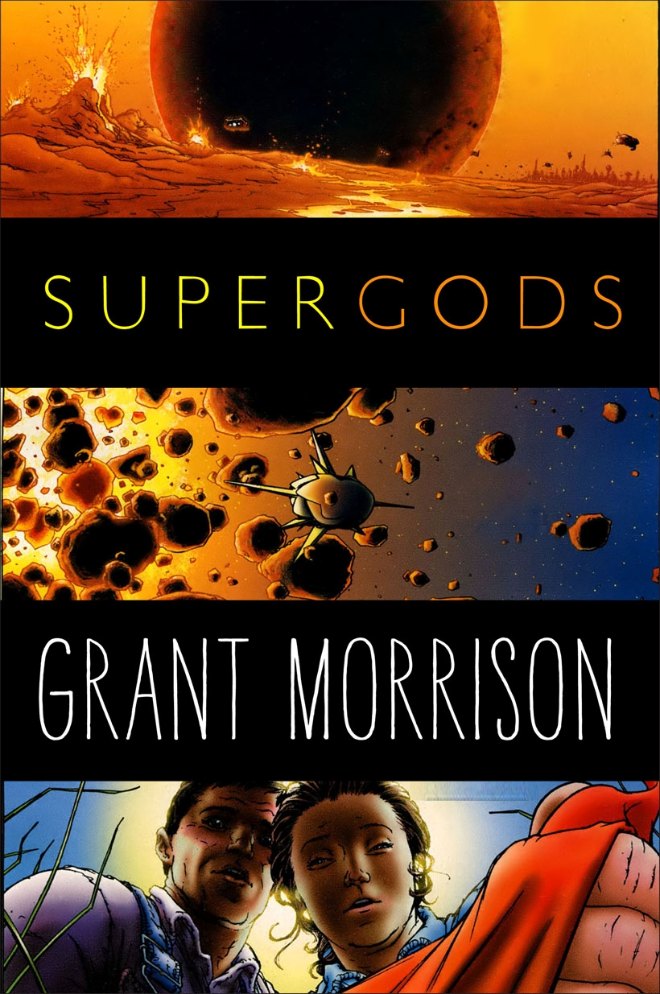

By Grant Morrison

Spiegel & Grau 2011

Grant Morrison is a decisive subject in comics. Many love his work. Many love to hate his work. Many just don’t know what to think of him.

What Morrison delivers with Supergods is a unique text about comics. It is part history, part deconstructionist analysis, part personal memoir, part reflexive view of his own work. It is a varied and interesting book that provides some fascinating insight into his ideas about the superhero.

The book follows a basic chronological structure that is divided along 4 ages: Golden Age, Silver Age, Modern Age, and Renaissance (starting the late 1990s). He deconstructs covers of famous comics such as Action #1, Detective #27, and The Dark Knight Returns #1. Certain key characters and stories are reflected on. It is not really any unique ground that is tread as far as the history of comics is concerned, were it not for Morrison’s uncanny intellectualizing of the materials in a way that augments their historicism with a psychological attention reflection on the material.

He notes the strange psychoanalytical current in the work of Mort Weisinger, the relative asexuality of Batman, the Sungod found in Superman. He is rarely critical of other creators or trends. He does occasionally question the validity of the “darkness” of post-Frank Miller comics. I could detect a bit of criticism of Mark Millar, but it was gentle compared to some of the rumors I have heard. True, he has come to praise comics and spread their gospel. In this day and age such an approach is refreshing.

His autobiographical contributions to the text outline his life experiencing the medium at first, then his own experience as a comics creator. While he does not go for explicit depth in any of his creations, he does highlight how his social life, relationships, occult interests, and general head space affected his work and in turn was affected by it. Many authors concede to a careful compartmentalization of their life and work, usually as a one-way flow where the work is affected by one’s life and not the other way around. Morrison differs in this regard because he would actively try to use methods of ceremonial magic in order to better understand the characters and emotions he was writing. He adapted many occult ideas to Constantin Stanislavski ideas of method acting and often became his characters as short experiments.

I feel there are some problems with the text. Morrison repeats himself at times, which I would venture is a result of writing the book in segments with a word processor. The book would have gained greatly from an editor who streamlined the text into a more linear structure. It is a bit noisome to read a certain twist of phrase about something and then read essentially the same comment in the next chapter.

Since Morrison has been on record for his drug use, it is no surprise that he notes a few places where they have influenced his work. Of course he discusses the alien abduction/mystical experience/mental breakdown he experienced in Kathmandu. It has been dramatically recounted in his famous Disinformation convention speech. Here he addresses how it had a unique influence on his perceptions of time and space. In anthropological terms, he seems to have undergone a “mazeway reconfiguration” where information is received from what is classified as an outside source (see the work of Anthony F. C. Wallace). This information can take several forms but usually it contains some ideas about reorganizing the world and a person’s relation to it. This often becomes the revelation that equips charismatic prophets to start revitalization movements such as the Longhouse Religion, the Ghost Dance religion, the Nation of Islam, Pentecostalism, the John Frum cargo cult, one could even argue Scientology. Here Morrison questioned his experience and chose to direct the new ideas inwardly to his own work instead of outwardly towards social reorganization and social action. In this sense I would compare his experience to that of Philip K. Dick…though I would claim that Morrison’s work was made better by his experience while I feel the work that Dick produced after his experience was not as good as his middle period (sorry).

Because of this experience and Morrison’s interests in and incorporation of the occult, the esoteric, and the avant garde there has been a matter-of-fact dismissal of his work as “drug” fiction and the idea that the reader has to be high on drugs in order to understand it. I have issues with this argument. One did not find such a dismissal of the avant garde in literature and art until the late 1960s. James Joyce, Akira Kurosawa, Jean-Luc Goddard, Salvador Dali, Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs (though because of the drug themes in his work he would be lumped into drug-influenced art)…these artists were not placed in a special category that precludes the use of drugs in order to enjoy their work, though after the emergence of the late 1960s drug culture, some of them were defined by it, often to the exclusion of their existence beyond a “drug-influenced” category.

This book goes a long way towards questioning that dismissal of Morrison as a simple drug fiend. It presents an interesting and intelligent man who still has the wonder of a little kid. His enthusiasm for comics is something that the form really needs. He appreciates the fun and insanity that is possible in comics and adds high concept ideas mixed with a child’s love of the absurd. He is not a cynical old man…and that is something to be admired these days.

Here’s the Disinfo speech again…turn down your computer, he screams really loud at the beginning.