by Kory Cerjak

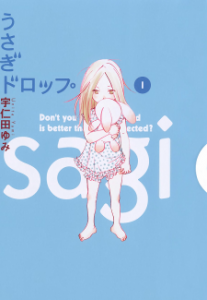

Life as a salaryman in Japan is already difficult enough. 30-year-old Daikichi works well past 7 p.m. each night and has way too much expected of him by higher-ups. Add in that he has to raise a child, who happens to be his grandfather’s love child, 6-year-old Rin. Such is Yumi Unita’s first (and so far only) manga, Bunny Drop (Yen Press).

Life as a salaryman in Japan is already difficult enough. 30-year-old Daikichi works well past 7 p.m. each night and has way too much expected of him by higher-ups. Add in that he has to raise a child, who happens to be his grandfather’s love child, 6-year-old Rin. Such is Yumi Unita’s first (and so far only) manga, Bunny Drop (Yen Press).

What makes Bunny Drop so endearing is how Unita slowly, almost methodically, characterizes both Daikichi and Rin. There are little moments woven throughout each chapter that give us more and more insight into Daikichi and Rin. Arguably the biggest moment comes near the end of chapter one. Daikichi is listening to his family argue about who will take Rin. Not because they all want her, but because no one wants her. It’s tragic to see a family brought together by a funeral be so divided about caring for a child. Daikichi, however, stands up, chastises his family for their behavior, and asks Rin if she wants to live with him. Unita doesn’t have many of these big moments throughout Bunny Drop (she prefers to use smaller moments, like Daikichi asking a co-worker how to raise a child or comforting Rin over wetting the bed) but when she uses them, it’s to perfection.

The pacing can feel slow at times because the story is about raising a child. It’s easy to both blast through a volume and not notice when you’re at the end and to read one chapter at a time, like it’s a day that’s just gone by. The story is so interesting because it’s focusing on Daikichi raising a child, which is often mundane and not filled with grandeur moments.

The comedy elements throughout the volume are from Daikichi fumbling over raising Rin or cutesy moments involving Rin. They weren’t really “funny” or didn’t resonate with me, but rather they’re used to break up the more serious and mundane moments of the volume. They’re situational comedy and the best part of them is the reactionary artwork Unita employs. Comedy is the weak point, but it fortunately doesn’t detract greatly from enjoyment of the volume.

Unita’s artwork is perhaps the most striking part of the volume. It’s basic in how she constructs faces, but complex in the little details such as hair and facial expressions. I was never wondering what face goes to what character simply by the faces, which is a problem some beginning mangaka have. Unita also uses a rather wide variety of clothes for the characters. Each character is never wearing the same outfit twice (unless it’s a business suit, like Daikichi’s). I think the most striking thing in the artwork is Rin herself. Comparing the first chapter to the last one in the volume, you can tell that she’s happier and more at home. Even when she’s uncomfortable around Daikichi’s parents and sister, she’s more timid rather than sad during grandpa’s funeral.

The one hiccup in the translation I saw was Yen Press deciding to not use translator notes on the page. On page 74, Daikichi makes a reference to his name being lucky, but English readers are left questioning why until we flip to the back where Yen has included those translator notes. These were the biggest moments that made me stop in the middle of the volume, because I was unsure of plays on words involving kanji or TV programs about samurai from the late 60’s.

Bunny Drop isn’t for everyone. Being a josei title, it has a relatively limited demographic (females 16-30) because most of their readership are studying for exams, trying to rise up the corporate ladder, or raising kids of their own. But josei titles often bring out the best and most realistic stories. What makes Bunny Drop special is that it’s focusing on Daikichi and not Rin. So many shojo manga are about teenagers growing up and so many josei manga are about adults trying to live in the real world by themselves and both shojo and josei are about trying to find love. Bunny Drop bypasses those story tropes and focuses solely on Daikichi raising Rin. And the story of raising a child is much more interesting than the story of growing up as a child.